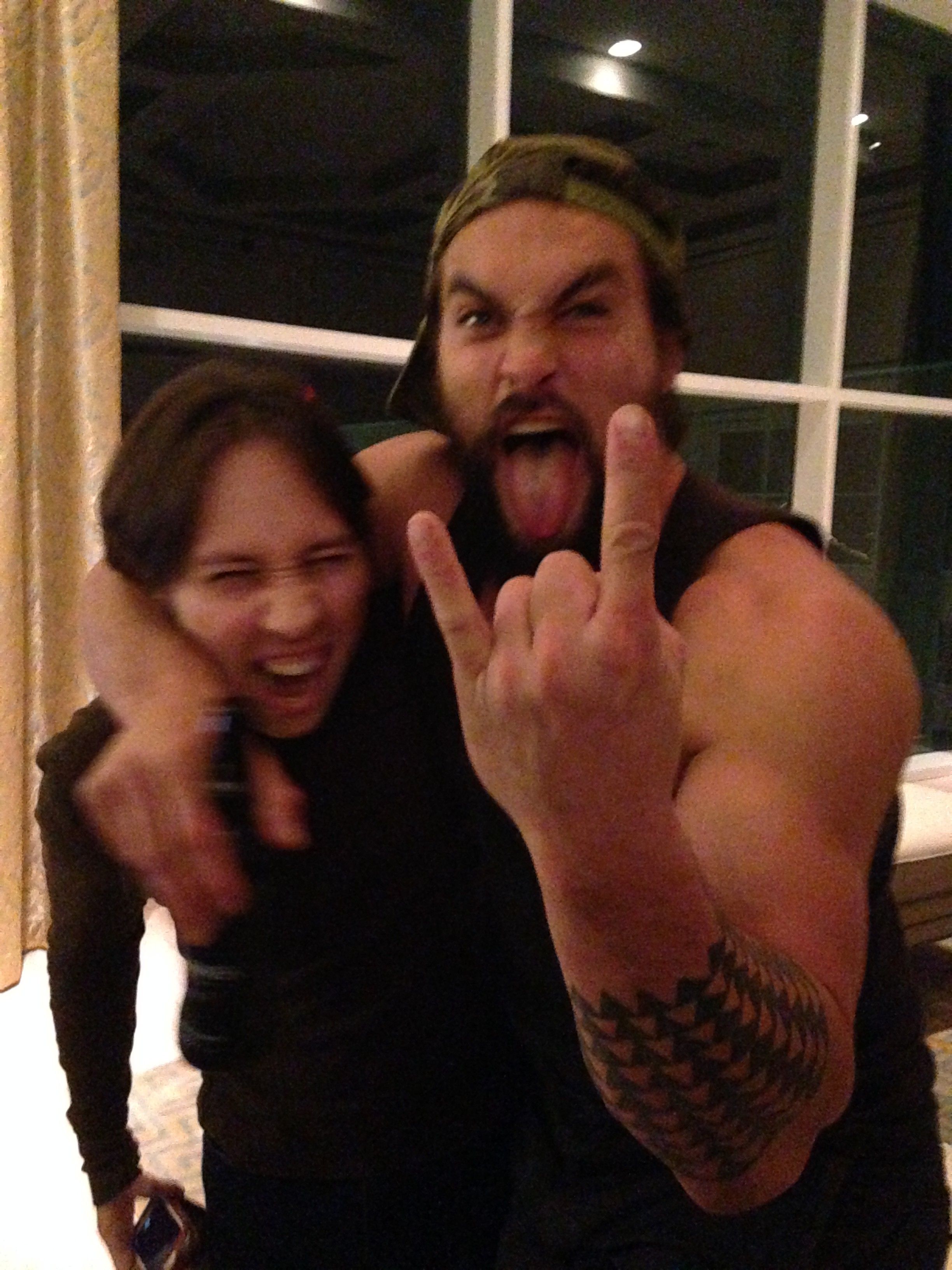

I’ve returned from SpaceCityCon, and had a bit to settle in here, so it’s time to start the year in Essosian conlanging. But first, I got a couple pictures of me with Jason Momoa (one below), who is, of course, awesome. The guy just absolutely loves life and is a ton of fun to be around—and he’s nice. He’s a good guy. If you get a chance, you should check out Road to Paloma, which he’s directing and starring in coming out this year (trailer here.

On my last blog post I got a request to translate “To boldly go where no man has gone before”—the old Star Trek slogan (the new one, of course, being “where no one has gone before”)—into High Valyrian. Seems like an odd pairing, but it is somewhat amusing for linguistic reasons. The whole “don’t split an infinitive” thing is one of those false rules that gets handed down from teacher to teacher, and the Star Trek motto is always held up as either an egregious example of the miscarriage of grammatical justice or as evidence that you can, in fact, split an infinitive. It is, of course, an example of the latter, with the whole “splitting infinitive” thing coming from the fact that you can’t “split” an infinitive in Latin, since it’s a single word. And Latin, of course, was George R. R. Martin’s inspiration for High Valyrian, in which you can also not split an infinitive, since it’s a single word. Consequently the translation won’t feature the same split that English does.

(Oh, and with my linguist’s hat on, I should say that “to x” isn’t actually an infinitive in English. The bare form of the verb is the infinitive. If you use it by itself, it has to be preceded by “to”, but you see the actual bare infinitive elsewhere—for example, after “will”, where you say “I will go with you”, and not “I will to go with you”. But that’s splitting hairs. [Ha. Split.])

Anyway, there were a couple of attempts to translate the phrase in the comments, but it’s missing some key vocabulary, so let me go through and do this, since it seems like fun.

Let’s start with the easy part. The “to go” part is going to be jagon, and it’ll be the last word in the sentence, so we can file that away and focus on the rest. There is no subject, which is handy, so let’s deal with the first modifier on jagon, which is “boldly”. In English, “bold” is pretty much a gentlemanly word for “brave”, so let’s stick with “brave”, which is nēdenka, in the nominative lunar singular (it’s an adjective). To turn that it into an adverb, you have to know the adjective class. Nēdenka is a Class I adjective, which means that it takes a suffix -irī to become an adverb. Thus we can change nēdenka to nēdenkirī and get nēdenkirī jagon. We can pop that bad boy at the end of the sentence and we’ve got the business part of the sentence done.

Now for the troublesome bit: Where no man has gone before. Again, let’s start with the easiest part. Since this is for a tattoo, I want to give you the option of saying “no man” or “no one”. This is a new clause of which the subject is “no man”, so we know that phrase will be in the nominative. To say no one, you’d say daorys, and that concludes that. To say “no man” specifically, you’d say dōre vala, but if you’d like to have a prolix gender neutral expression, you could say dōre issaros, which would be “no being”. Whichever one you like, though, you’re now done, because their citation forms happen to be the forms that are necessary for the function the “no man” bit plays in the clause.

For the verb, you’d use the perfect. In Low Valyrian you might use a different construction for “has gone” as opposed to “went”, but in High Valyrian the two are conflated. The form of the verb is istas, so the phrase becomes daorys istas (or dōre issaros istas or dōre vala istas), which is “no one went” or “no one has gone”.

Before getting to the clause-linking part, Mad Latinist conjectured that you might be able to use naejot to mean “before”, but Zhalio noted that this was unlikely, given its etymology. In this case, Zhalio was correct. You can use naejot to mean “before” for the meaning “in front of”, but you can’t use it for the temporal “before”. For that, in fact, you use gō. You might remember gō from such meanings as “underneath” and “below”. It also means “before” in the temporal sense. This is a part of a guiding metaphor High Valyrian employs where height is associated with time depth. Consequently, things that happen before the present are below the present, and things that happen after the present happen above it (tolī as an adverb or toliot as a postposition). The postposition gō can be used as a postposition or as an adverb (just as with naejot), and so the expression now has become daorys gō istas.

Now for the last bit. Mad Latinist used the relative adjective lua in his translation attempt, which is a good guess, but doesn’t work in this instance. Hopefully the difference can be explained succinctly using these three examples:

- Skoriot istas? “Where has he gone?”

- Skoriot istas ūndan. “I saw where he went.

- Istas luon lenton ūndan. “I saw the house where he went.

The difference here is that in the second you’re not really modifying “where” the way you’re modifying “house” in the third, if that makes sense. Think about something like, “I know who wrote Catch-22” and how it differs from “I know the guy who wrote Catch-22“. The first is a statement about a question (e.g. “Who wrote Catch-22?”), whereas the second is an actual assertion about someone you know (in fact, you’d use two different verbs in Spanish for this). That is, it brackets thus:

- I know [who wrote Catch-22].

- I know [the guy [who wrote Catch-22] ].

Hoping this makes sense. Consequently it’s not really a relative clause. Rather it’s a self-contained clause that is the object (or topic) of the matrix verb.

So.

Back to our original translation request: To boldly go where no one has gone before. This is what we’ve got:

- Skoriot daorys gō istas nēdenkirī jagon.

And there it is.

I suppose if you did want to mimic the so-called infinitive split, you could put nēdenkirī in the front (something like “Boldly where no one has gone before to go”), but I wouldn’t recommend it. And, of course, you can substitute dōre vala or dōre issaros for daorys if you so choose. So there you go, Monserrat Vargas! If you get a tattoo, please send us a picture.

Also, a couple general notes. I’ll have a big announcement later this month, but I did want to note that this year I’ll be working on the show Dominion on Syfy. No major info on that yet, but I’m working on an a posteriori language for the show (my first, though not as stringently a posteriori as a language like Brithenig or Wenedyk). It’s called Lishepus.

Otherwise, happy new year! Stay tuned for the yearly Dothraki Haiku Competition. It’s coming!

Hmmm… so when you use the question-construction rather than the relative-construction, there’s no way to assign a case to the clause, right? It’s accusative in “I saw (where he went)”, but allative in “To go (where no-one has gone before)”.

In German, I’d use the relative construction to literally translate the Trek line: »…und kühn dorthin zu gehen, wo noch nie jemand gewesen ist.« ML, how would that work in Latin?

(Of course, the line they actually used for the Series is “Die Enterprise dringt dabei in Galaxien vor, die nie ein Mensch zuvor gesehen hat.” Which is woefully inaccurate, since 99.9% of all Star Trek episodes take place in the same old galaxy. I think this an example of the common misconception that “Galaxie” is a synonym for “planetary system”.)

Yes, this is the case—and is actually quite reminiscent of Castithan, of all things. It’s its head-final nature showing up.

I got my tattoo yesterday! I have pictures! Just let me know how you’d like me to send them. =D

<:o <:O <:O <:O ZOMG! You can e-mail by following this link. (I’d just write out the e-mail, but that page has a special spam-blocking script on it, so I always just link to the page.)

“Lishepus” — hmm, Google tells me they used Enochian for the movie Legion, upon which Dominion is based. Looking at an Enochian wordlist, I only see LIXIPSP as a possible root. The meaning of that is apparently “the warden of the Aethyr named ‘BAG'”. Oof — I don’t suppose that’s it…?

Anyway, welcome to postlanging. ;o)

In this case, not related to Enochian at all. We went a different route (a much more fun route). Can’t wait to talk about it.

It will be very interesting to see you “postlanging.”

Great to see a new post here! And of course new HV information, which, as you know, I gobble up. I have a lot of random points here, so forgive me for jumping around from paragraph to paragraph. Heck, why don’t I do this in sections?

1. Infinitives:

One often hears that Latin is the origin of the split infinitive rule, and it’s certainly true for a number of other prescriptions of English grammar. But when I mentioned this in one historical linguistics class, the professor (for whom this was clearly a pet prescription) claimed that allegation was false, and that in fact the reason you’re not supposed to do it is that the “to” is historically identical to the preposition. And since you can’t say “go to directly jail” you can’t say “to boldly go” either. His example is manifestly correct, but I don’t know whether his explanation is or not—he was, after all, a professor of Afro-Asiatic languages, not English.

I’ve heard the bare English infinitive (without the “to”) called a “supine infinitive,” but of course that’s a term brazenly modeled on Latin (well, Latin has a “supine” if not a “supine infinitive.”) It’s interesting that in Hebrew the infinitive developed nearly exactly the same way (or rather the English infinitive developed the same way as the Hebrew!), namely that in most conditions where you would get an infinitive it has the proclitic preposition lǝ- meaning “to,” but there are some contexts (almost exclusively in Biblical Hebrew) in which it occurs bare.

2. Adverbs

You had previously said that the adverbial suffix was sometimes -ī and sometimes -irī. I can’t believe we never figured out that this was linked to adjective class. Talk about falling down on the job!

3. “No man”

This almost seems like a case where you’d want to use valar. Obviously we couldn’t use the aorist here, nor the past habitual, but could you say valar gō istos daor? What if we get really wild and say dore valar gō istas?

4. Postpositions (and the adverbs thereof)

Should I take this to mean that naejot does actually come from naejos “breast” (as Zhalio said) rather than naejon “front” (as I said)? Or did we somehow get our wires crossed, and those aren’t actually two separate words?

Fascinating about the spacial metaphors. Of course Valyrian doesn’t seem to distinguish “locative” adverbs from “allative” ones (that is, for instance, so far as I know, naejot can mean either “in front” or “forwards”), so that means there would be no way to distinguish “go below” and “go before,” at least in this phrasing, right? Not that that’s a problem, anymore than English “go before” which also means “go in front.” I suppose if you wanted to make a distinction you could do something like *gōvistas?

Is there some sort of connection between all these tol- words? We have tolī/toliot “above, after,” tolie “other,” tolmiot “far; across,” and tolvie, tolvys “every,” “everyone.”

5. “Where … has gone”

Interesting. In Latin this is called an indirect question, and it’s been on my list forever to ask you about (granted, one normally refers to an “indirect question” when it’s dependant on a verb of saying, thinking, or perceiving, but it would apply even in a case like this, I think). And hey, Zhalio asked, so I’ll elaborate: in Latin an indirect question requires a subjunctive, so “Fortiter ire quo nemo antea ierit (perf. subj.) If you do it as a relative clause it generally does not use a subjunctive (but I confess that when Latin relative clauses do and don’t take a subjunctive is a particular weakness of mine. I find when I’m speaking Latin casually I put nearly every relative clause in the subjunctive, then wince as I realize that was probably wrong!)

It appears that no subjunctive is required. This is interesting not so much because of the Latin as because of the HV: We know that indirect statements sometimes take a subjunctive: Morghot nēdyssy sesīr zūgusy azantys vestras. (But not always: Dārys issa vestris.)

(Side note: indirect commands might take an infinitive, at least if Mentyri idañe jevi ivestrilātās keskydoso gaomagon is any indication.)

So if this were a true indirect question, like say “She asked where they had gone,” or “She asked whether they had gone where no one had gone before,” would the construction be any different?

6. Relative clauses

It is a well-known fact that in HV the relative “pronoun” is actually an adjective that modifies the head noun. This means it is always marked for the case required by the main clause, rather than the subordinate clause. This can lead to ambiguities of a sort which Latin hates (but many, many languages are just fine with)

As I wrote on the wiki:

The example of Istas luon lenton ūndan would seem to confirm this (granted, there are not many other possible meanings in this sentence: “the house where he was,” I suppose, but that’s not really the fault of the relative, “the house inside which he went” is not terribly likely. And I guess if you wanted to say “the house from which…” or “the house around which…” or whatever, you would again use a locative-applicative verb.)

But supposing you had a relative clause you wanted to clarify. How would you do it? Again quoting the wiki:

Thanks again. I have a feeling this comment is too long (and maybe complex) to expect an answer to everything, so feel free to answer partially.

Hahaha, I just noticed that in my bird-on-a-house example I used undon rather than undan. So apparently Latin isn’t the only language where I gratuitously put relative clauses in the subjunctive!

I’ll admit that I can’t be sure if the Latin historical origin is actually true or not, but I can be sure that your professor’s reasoning is flawed. Not only can you not say “go to directly jail”, you can’t say “the directly jail”. The reason is that an adverb can’t modify a noun. It can modify a verb, though. “To boldly go” has a near identical structure as “to dank prisons”—namely, preposition modifying an XP which consists of modifier followed by X. What would actually kill this thing is if you weren’t allowed to say “He boldly entered the room”.

I can understand why you’d think to do so, but I wouldn’t here. I certainly hope it wouldn’t be English interference, but to say dore valar seems wrong for this. I like the idea of the solitary man not trekking through space. Of course, I prefer daorys, anyway, but just saying.

At this stage, you can’t look at either one and say which came first. But in prehistory, the root was probably one which became naej-, and probably first meant “chest”, but that would’ve been quite a while ago.

And High Valyrian doesn’t distinguish a lot (something which should become more and more obvious the more you look at these relative clauses). But the locative/allative distinction isn’t the same distinction present for underneath/before. That one is simply a semantic/metaphorical distinction. So, no, there is no way to distinguish.

Not required, but allowed. If you were to use the subjunctive here, it’d be more, “To boldly go where no man would have gone before”. This is more direct. So, yes, the subjunctive works differently in HV than it does in some languages that have them (it’s more of a late subjunctive, I want to say, where it has more affective uses than syntactic uses).

To this let me just say: yes. This is the case, and it was intentional.

It’s also too long/detailed to explain in a comment how this works, but I promise I’ll do a post later just on relative clauses in High Valyrian. (Incidentally, relative clauses in AV are much easier, thanks to the magic Ghiscari ez preposition which I love dearly.)

First of all, thanks for replying! I know that was a long comment (at least by the standards of the present day).

Good point on “go directly to jail.” I’m not sure I’ll have to think more about that last example.

I skipped a few steps in my reasoning there, which I think made my comment look dumber than it actually was. What I meant was more like this: if Valyrian did distinguish locative and allative adverbs, then you would have two forms:

• One locative form, which would mean “beneath, under, below” (as in “he stood below”), and “before.”

• One allative form, which would mean “downwards, under, below” (as in “he went below”).

The only context in which the allative would make sense with the meaning “before” is in time travel! Otherwise it only makes sense in the locative version.

This distinction would be particularly salient in this sentence, since it features a verb of motion:

• The allative meaning pretty much has to be spatial (“He went under.”)

• The locative meaning could be spatial (“Down below, he went”) or temporal (“He went before.”) But I gotta think the temporal meaning would be more common.

So I’m not saying that semantic vs. metaphorical is equivalent to allative vs. locative, I’m saying that if HV did make that distinction (and so far as I can tell it does not!) then it would give you a clue as to the semantic vs. metaphorical use.

But assuming HV does not make that distinction, this is all academic anyway.

Ah, actually if you use a relative clause in Latin, the indicative/subjunctive distinction works quite simlarly. E.g. the whole “relative clause of characterstic” phenomenon that drives me crazy.

In fact, it seems to me that to the Ancient Valyrians the negative uses of the “subjunctive” would have been more salient than the “hypothetical” uses… they’re certainly far more frequent! In native terminology I bet they would have been not indicative and subjunctive, but something more like “declarative” and “negative.” (Well, “negative” might be too strong, but I think you get my point.)

Is this a typological thing, since Japanese has the same ambiguity?

Definitely looking forward to that!

AHA! So ez does indeed function as a relativizer (in addition to its many other uses!) I was wondering, since in every instance we have, translating it “of” seems to work, even when it is translated with a relative (possible exception: Ji broji ez bezo sene stas qimbroto “The name this one was born with was cursed,” which is complicated by the fact that I—and, so far as I know, know other Valyrianist—have not yet figured out what sene is.)

Of course AV seems to also be capable of forming relatives by gapping, e.g. Bezy sa ji vala yn tehtas angez rukla “This is the man who gave me some flowers.” Oh, that reminds me of another thing I’ve been meaning to ask: you have tehtas here (as if from *tektas), but teptas elsewhere (the expected outcome). Is this a legitimate variation, or is one of those forms wrong?

It’s supposed to be tehtas (stops > fricatives before stops; *f > h).

OK. But then what happens to t? Does it turn to s?

Fyi I got teptas from the line Y Torgo Nudho sa ji broji ez bezy eji tovi Daenerys Jelmazmo ji teptas ji derve. Dialect variation? Or maybe he’s just echoing Dany who just used that word in HV?

That was the idea, but unfortunately I didn’t do enough of it. Mainly you see Dany using AV words in her speeches, but I did intend to have people like Grey Worm do “up talk” when speaking to Dany, but I ended up forgetting about it a lot, so it doesn’t appear much. I should’ve just gone back and undone them, but a few crept in. Oh well.

OK, then that makes perfect sense. Thanks.

OH! Also, very important: in your final translation you left off the gō!! I wouldn’t want Monserrat Vargas to leave that off the tattoo by accident (if he chooses to leave it off, that’s another thing).

BTW, what’s the difference between bē and toliot? Is it “on” vs. “over”?

Heh, heh. I will note that my wife actually noticed this before you (or, if you will, you gō).

/rimshot

“On” vs. “over” is a good way to distinguish the basic functions, yes.

The use of above/below for time is pure genius. I’ve always thought of that as a binary decision in conlanging: Either the past was before or behind you. (In Oro Mpaa, I used upstream/downstream instead, but that’s basically the same thing as before/behind.)

dōre vala

Oy, we have dore down with a short o. Does the usual rule apply here? (Namely that if you’ve given us a word with inconsistent macrons, we should assume the form with the most macra is correct )

)

It’s definitely supposed to have a long vowel. If you took it down with a short vowel from one of my posts, please let me know so I can correct it! Again, part of this is working with Final Draft, that simply can’t work with vowels with macrons, but I think it also bespeaks the romanization choice. While vowels with macrons are more elegant, in my opinion, and more reflective of the phonemic nature of the long vowels, it’s easy to forget a macro; very hard to forget a doubled vowel. Maybe doubled vowels are just better for this…

Hmm, so far (I’ll check in more detail tomorrow) I’m not finding any where you slipped up, except the dōrior dārion phrase you gave in that one interview, (but that one so does not count), so I almost certainly botched this one on my own. Sorry!

Dothraki:

Elat k’athivezhofari rekkaan vosak ray e hatif ajjini!

?

I guess ray could be dropped without much difference and perhaps ajjin could be changed to a copy-pronounish mae.

It’s interesting to note the difference between relative and not relative “where” discussed above. I tried to inquire about how this works in Dothraki just a short while ago, and if I understood right, neither would count as relative use in Dothraki: as long as the word is rekke, the clause defaults to SVO word order and is not a genuine relative clause.

Elat rekkaan vosak e. – To go where noone went.

Elat gachaan rekkaan vosak e. – To go to a place where noone went.

Or could you go something like “To go to a place to which noone has gone before”?

Elat gachaan rekaan e vosak.

Elat gachaan rekaan e vosak mehas.

…Alright. Am I just terribly confused or are these ruminations in any way relevant or sustantial?

—-

I have a vague memory that in Valyrian some woman words would have the same-ish gender-neutral dimension as english man. So could “To boldly go where no man has gone before” be translated through “To boldly go where no gal has gone before” if the kinda sorta but not really gender neutral sense was to be maintained?

—-

I too am bummed about the graffiti. We have seen before in the treatment of Qarth that the creators are willing to compromise the world vision when foreign languages don’t serve a major story purpose, so it’s not a big surprise. Still, the wall writing is so small detail that it could not have been a big strain to do it right.

Valyrian in latin letters would have been a passable solution. It’s been set up, so it would have probably been quite easy to pick up. Valyrian glyphs might have actually looked a bit bogus skrawls thrown into a graffiti without any itroduction.

Also, some fan-fodder lost-in-translation allusion to “ROMANES EUNT DOMUS” would have made my day.

The rule seems to be that a word that refers to a female human encompasses both genders in the collective. So:

ābra “woman” → ābrar “people”

muña “mother” → muñar “parents”

riña “girl” → riñar “children”

(However, we’ve also seen the singular riña used to mean “child,” in a context where taking it to refer only to girls could have irreversible consequences!)

So presumably if we want to do that here, we wind up in the same situation as my proposal above to use valar, which DJP said he’d prefer not to do.

Edit: how did I get so caught with rekke? The relative pronoun should be fini, and thus at least the last two should, I think, be

Elat gachaan finnaan e vosak.

Elat gachaan finnaan e vosak mehas.

…which is interesting in that the difference between finne and fini seems to be lost.

Edit again: hell no. I’m confusing too much stuff. This is going nowhere. Finnaan is animate, finaan inanimate.

You were right with rekkaan and also right with finnaan.

That would be more informative answer if I had stumbled less.

Are all four

Elat rekkaan vosak e.

Elat gachaan rekkaan vosak e.

Elat gachaan finnaan e vosak.

Elat gachaan finnaan e vosak mehas.

sound costructs and in the regular word order, then?

And since that should mean that finnaan is allative from finne, does that mean that the “to which” syntax I tried to construct (but fumbled) does not work? Because it should IMO be

Elat gachaan finaan e vosak.

Elat gachaan finaan e vosak mehas.

Actually, the second one doesn’t work (Elat gachaan rekkaan vosak e). Rek doesn’t work as a relativizer.

Also, finaan does work. I was thinking of something different.

In poetic speech or in non-initial clauses, VSO remains a stylistic variant in Dothraki, so you could do either.

Regardless, It’s nice to know, when you’re going stylistic and when following the norm.

I’m still trying to figure the inner workings of the language – best to my ability.

Hello travelers. Being that it was Poe’s birthday (Jan 19) I was wondering if anyone is also a fan, and if there is a translation of his work “A Dream Within A Dream” available in High Valyrian…

Today, the 20th, is also Mr. Peterson’s birthday!

We don’t yet know the word for “dream”… or, honestly, “within” (unless hedrȳ would work?)… so translating the title (let alone the whole work) is currently impossible.

Unless of course, the creator of the language decides to drop some hints for us

Then there shall be great celebrations for both great men!

At least there is a word for dream in Dothraki Perhaps that is more feasible?

Perhaps that is more feasible?

Huh; in my English classes, the Star Trek quote was held up as an example to the point of “of course, we break this rule all the time—and it’s not always wrong to do so.”

But if I can stick up for the rule (and for sticklers), check out what it sounds like when the sentence is corrected:

“Boldly to go where none have gone before.”

Now, maybe it’s just to my ear, but that sounds superlatively more elegant than Shatner’s clunky original line.

Well, the point is that the sticklers were wrong. It’d be kind of like calling someone a stickler for saying that you’re supposed to eat soup with a fork (i.e. they’ll say that now people are lazy and it’s popular to use a spoon, but they’ll continue using a fork to eat their soup like you’re supposed to, thank you very much!). It’s silly.

The important take away from your example is that we can do either. The adverb can modify the verb directly, or be placed at any point where an adverbial clause can go. And it really is a matter of taste. I think that variant sounds awful and is clearly the inferior of the two. This one, though, seems all right:

“To go boldly where no one has gone before.”

Also by fronting “boldly”, it destroys the parallel structure of the success non-finite clauses. In my opinion, of course. All of this is purely a matter of taste, and not a matter of grammar.

Well, yes—I suppose I could have been clearer. (Really the clearest I could have been would have been to cite Orwell, Pol. & Engl. Lang.) Whenever you think of ways to write, remember there are always others. (Ten points if you pick up on THAT reference.)

As to the metaphor of soup and the fork… no. Eating soup with a fork has never been the rule. You might have gotten somewhere by comparing to the rule no longer acknowledged in America of using the fork with one’s left hand. But really, can we just acknowledge that we’ve both heard the words prescriptivist and descriptivist before and agree to skip the merry-go-round?

I only see one clause following an infinitive phrase and don’t see the parallelism problem to which you’re referring. Also, I shall never accept “front” as a transitive verb, so shame on you.

I’m pretty sure the fork thing was meant as an impromptu made-up example.

As for “Boldly to go…”, that sounds goofy to my ear. It reminds me of an inscription I once read on a plaque in Scotland: “I to the mountain lift mine eyes…”

I really don’t think you understood my point.

As to what sounds goofy and what not, I heartily agree with David Peterson: It’s a matter of taste. But as to your example, I suspect you’re conflating the infinitive “to” and the prepositional, if that’s what it brings to mind.